Nicks and Dings

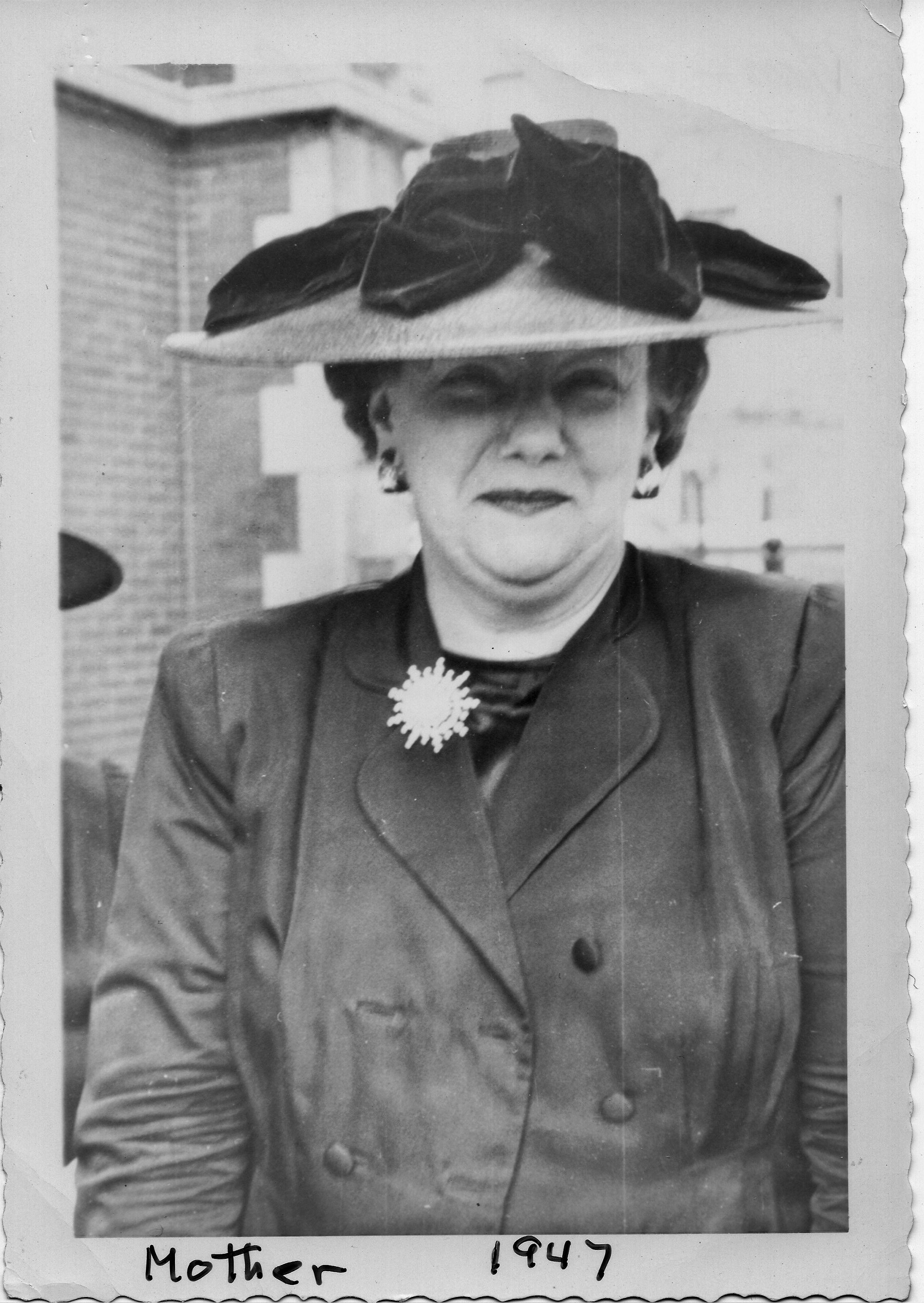

My mother, Barbara Fallon Humphrey (1928-2021) treasured this hat form and it was in her sewing room throughout my childhood. Now it sits in my sewing room, often displaying a charming hat. It originally belonged to my grandmother, Friederica Hermes Fallon (1898-1961),“Nanny” to my 5 older siblings, but called Frieda by everyone else. I was named for her as she died of ovarian cancer at the age of 63 before I was born. Frieda did not have an easy life. She had little formal education, married at the “old maid” age of 29 and was left a single mother of two daughters by age 37. Mom always spoke of her mother’s ridiculously fancy taste, often using the adage “champagne taste with a beer pocketbook”. Our joke was that this was clearly an inherited trait as Mom, too, enjoyed beautiful things, and “the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree” applies here to me as well. I have very few things from Nanny, and the hat form reminds me that while Nanny’s life was difficult, she used her talents to add beauty in the world, and supported her girls while doing so.

Hat forms were used to mold material into a specific style hat, and workshops would have many different sizes and shapes of hat forms, some quite elaborate. My grandmother’s form is a fairly plain one, carved from a single piece of wood. The traditional material used for hats was felted animal fur, a process developed in the 17th century. Hatters used mercuric nitrate to separate animal fur from skin, creating a felted fabric. This process was called “carroting” because mercury, often derived from cinnabar, turned orange when liquid. By the 1800s it was known this resulted in “mad hatter disease” - essentially mercury poisoning, medically called “erethism”. Mercury use for hat production was banned in Europe by 1900, but hat production in United States involved mercury up until 1941. It was stopped “mainly due to the wartime need for the heavy metal in the manufacture of detonators”. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erethism). The main risk for hatters was the absorption of the vapor, as mercury’s relative chemical inertness makes it unlikely to be absorbed through contact. Which is certainly a good thing for owners of old hats, and possibly old hat forms pre-dating 1941. As my grandmother only had the one hat form, I suspect she was a “milliner” not a “hatter”. Hatters made the actual hats but a milliner did more decorating of hats – adding lace, feathers and other embellishments to an existing hat. The nicks and dings in my grandmother’s hat form would have come from her using pins to hold things in place as glue dried or needles from sewing bits and pieces together. I do wonder, however, if her early death from cancer may have been attributed to working with hats during the 1930s, with the corresponding mercury exposure.

I also have a set of 8 needlepoint chair seat covers done by my mother and grandmother in the 1950s – thankfully mercury free. A brother, who inherited the dining room set, removed the covers recently, “modernizing” the chairs with new upholstery. He planned to throw out the set and I paid $14.55 to have him ship them to me. Having been in use for over 60 years, they desperately need to be washed. This requires a blocking form – another project for hubby! (see prior blog post: catawampus-framing). While I could ask my husband to create something for me to use, the basic issue is I don’t have a use for 8 seat covers at present. Hopefully they will be put to use someday as they are a testament to my mother’s and grandmother’s needlework skill, done on a very fine canvas with tiny stitching. Accomplishing one of these would likely cause me to lose my eyesight – finishing eight boggles the mind.

I also have a rose applique quilt made by Nanny, which was from a 1950s era “kit”. Nanny started 3 of them – one for each of my 3 elder sisters, but only finished one before her death. My mother stored the tops in her bedroom closet during my childhood. I recall this specifically because our Siamese cat could often be found curled up on the pile on the closet shelf! Eventually Mom cleaned off the accumulated dirt and cat hair and finished the applique work, sending them out to be “professionally” quilted in the 1970s.

When hubby and I were newly married in the late 1980s, we would go antiquing in Chicago - shops filled with treasures snagged in the rural areas of Illinois, Wisconsin and Indiana. At one store we found a lovely iron bedframe designed with circles of roses. The frame became our guest bed, displaying my grandmother’s quilt for years. Sadly, guests outgrew double beds in the prior century, so the iron bed was set up in our daughter’s room for a spell, though getting that old wood box spring up our staircase involved some serious engineering. Adult daughters with significant others do not like double beds any more than prior-century guests. So out to the barn it went, with the darn box spring being chopped up and thrown out. In case anyone is worried, Mom gave the remaining two quilts to a different brother for his two daughters. Unclear what happened to them, but I hope they were saved.

While there is no paperwork from Frieda, and very few photographs, I do have my Mom’s birth certificate from Chicago. The document says her father, Martin Fallon, was from England, and was 34 when Mom was born. He had been in Chicago since 1921 and he and Frieda married in 1927, though I do not know how or where the couple met. In truth, Martin was from Boston, and was wanted for some insurance fraud he skip town to avoid. He left behind a wife and 3 children (including another daughter named Barbara), who all moved in with his mother, my great grandmother Julia Fallon, when he disappeared. Julia Fallon hired an investigator to find her missing son. As he had served in WWI, driving ambulances in France, his name was entered in a federal data base for veterans registering for benefits. My mother suspected her father’s actual name may have been George Fallon, though upon arriving in Chicago in 1921, he went by Martin Fallon, which was his father’s name (my great grandfather).

Eventually the 1930’s depression hit, and money became an issue. When Frieda insisted her husband sign up for benefits from the veteran organization, she had no way of knowing those benefits would not benefit her in the slightest. Once he did, the investigator in Boston was notified. Soon some communication was sent, though I do not know how this transpired. At this point Frieda learned her husband had another family in Boston. She begged him to divorce the wife, allowing him to stay if he did so. He said he could not as she was Catholic, which is a bit ironic as my grandmother – his “second” wife – was as well. He left soon thereafter, and my grandmother moved with her two young daughters to live with her eldest sister Frances (1888-1952) and her family. Besides the financial impact, and social stigma, Frieda was distressed her daughters were “illegitimate”. While the label is not as devastating, nor really used much in our day, in her era it was significant. Frieda’s brother, Joseph Hermes, a Chicago judge, arranged for his two nieces to be legally “legitimate”. No clue what that would have entailed, but it was important to my grandmother and my mother.

To support herself and her daughters, Frieda got a job teaching sewing at a high school, and had a side business decorating hats for clients. I suspect Frieda learned to sew from her mother, Katherine Becker Hermes (1834-1931), a woman who arrived in this country from Germany with a sewing machine (see prior blog post: hemming-my-history). It seems a creative sewing talent runs through this line of women. Frieda was very talented, making all the family’s clothing and using her skills to earn money. Mom was also a remarkable seamstress, but her creative art form was knitting. I turned my focus to quilting, and it suits my brain which loves to “organize” and fit things together. My grandmother’s hat form, sitting by my side while I work in my sewing room, reminds me that life can be a struggle, full of nicks and dings, but creating beauty helps brighten any difficulty. And a little financial input never hurts.