A Moment Of Truth

When I volunteer at the thrift store, I often come across things that intrigue me. Not always officially “art”, and in this case I would say more an “artifact”. There was no way I was passing up this magazine when I spotted it. I did not know, however, just how much an artifact the piece is - as far as I was concerned, any Ms. Magazine from the 1970s would be interesting. The magazine was poorly mounted in a frame, with the insides slipping off the binding, and thus a bit catawampus. I asked the manager to put a price on it for me, and was a tad worried she would recognize what it was, pricing it high, or holding onto it for more research. She did neither, and I purchased it for $15.

According to Merriam-Webster online dictionary, an artifact is:

a. a usually simple object (such as a tool or ornament) showing human workmanship or modification as distinguished from a natural object.

b. something characteristic of or resulting from a particular human institution, period, trend, or individual

c. something...associated with an earlier time especially when regarded as no longer appropriate, relevant, or important

This magazine actually hits all three definitions. It is a simple object: a published magazine, filled with writings and ads. It definitely qualifies as resulting from a particular human period – the 1970s United States, with the feminist push for equality and rights. But that last definition made me pause. Is the “housewife’s moment of truth” no longer relevant or important in our society? Has much changed over the past 50 years for women and their rights? In researching this piece I came across a quote which also made me pause: “While on a personal level feminism is everywhere, like fluoride, on a political level the movement is more like nitrogen: ubiquitous and inert.” (Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future, Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards). American women today seem to accept they have rights and yet do not realize just how fragile those rights are historically. And don’t get me started on fluoride – but an apt analogy as it too may soon go the way of the dodo. Gloria Steinem and her magazine paved the way for women to ask questions and make demands, but the backlash was severe, and continues to be so.

Steinem was working at the New York Times Magazine office in the early 1970s and was asked by her editor to either “go to a hotel room with him in the afternoon, or…mail his letters on the way out.” She adds, in an interview with the Smithsonian “I mailed his letters, but thanks to changed consciousness, I realized it wasn’t right. I didn’t have to put up with it. I could speak up about it.” Basically, she quit (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/explore-the-founding-of-ms-magazine). I worked at Chemical Bank in NYC 15 years later and, sadly, experienced similar comments. I actually filed a complaint at the time, and the bank executives had a conniption fit, making the trainee class I was part of learn about sexual harassment. That, however, did not mean sexism in the corporate world simply went away if my experience in the banking world through the 1990s is any example.

Back in the 1970s, the news industry would not print any “real” stories about women. “The male editors of the major women’s magazines—called the “seven sisters,” like the colleges—would not accept pitches that did anything other than advise readers to be better, happier, more productive housewives and mothers” (https://yalereview.org/article/closer-look-ms-magazine). After quitting, Steinem began work in her apartment with female journalists and politically active feminists to create a women’s magazine. It was an uncomfortable gathering, and eventually the more “militant” feminists parted ways as they did not like to cater to the advertising world (run by men). “There was no budget to advertise the preview issue, and much of the press attention that it elicited was negative…The magazine’s own editors planned for slow sales: when a stand-alone edition of the preview issue appeared in January, it was labeled “Spring 1972” so that it could stay on newsstands for months. As it turned out, there was no need for such hedging. The issue sold out in eight days.” (https://yalereview.org/article/closer-look-ms-magazine).

My thrift store find is one of those issues, preserved most likely by a woman for 52 years. Hubby joked that the woman must have only had sons, who, while clearing out their mother’s stuff, couldn’t imagine why she kept a Ms. Magazine from the 1970s in a frame. It amuses me that the magazine I found is actually valuable, so nah nah na nah nah boys. Your mother was a wise woman.

This particular one is in remarkably good condition, complete with all those “blow in” inserts. Honestly, that impresses me the most as I promptly tore all those things out when I read a magazine. Particularly back in the 1990s when perfume companies used the blow ins to promote fragrances, making the magazines rather pungent. I only just found out those things have a name, and a rather odd one at that. The term derives from the fact that the machines, used for stapling the magazines, blew in the cards…thus they were referred to as “blow ins”.

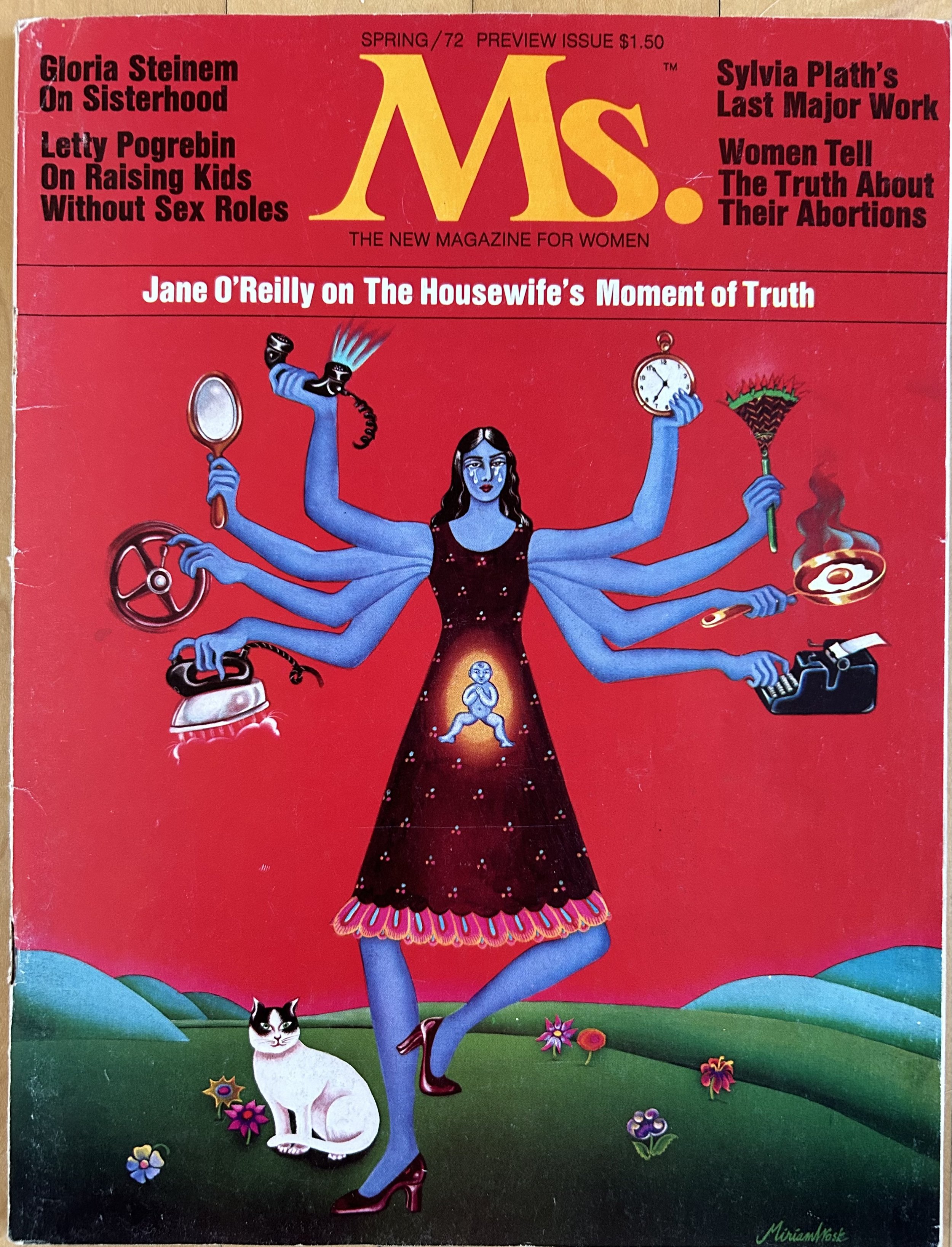

The magazine’s cover art is by Canadian artist, Miriam Wosk (1947-2010), patterned on the image on Krishna, the Indian god with many arms. Krishna, the Hindu god of love, compassion and protection, is often depicted as blue. Wosk’s version has a blue woman juggling the demands of work, marriage, and motherhood. The idea being “having it all” was a serious juggling act, and not at all easy. It was only in the next year that the U.S. government allowed the designation “Ms.” to be legally used by a woman. Prior to then women had to use “Miss” or “Mrs.”, as though a woman’s marriage status was all that could define her, compared to a man who is always “Mr.”. Okay etymology fans, did you know “Mrs.” was originally short hand for “mistress”? Grant you, back in the 1500s, it was an honorific title, specifically for upper class women, not the slightly risqué idea of a woman having an affair with a married man we tend to interpret it as. Over time, “Mrs.” was associated with women who had husbands, and thus were married women. The idea of a woman’s marital status being irrelevant to the way she is addressed only came about after Ms. Magazine created the honorific “Ms.”

When I was first married, my mother mailed me a letter, addressed to Mrs. “Hubby” Jarrett – as though Erica now didn’t exist. I made it very clear to her I was NOT Mrs. Hubby Jarrett, I was Erica H. Jarrett, or Ms. Jarrett if need be. That was in 1987 mind you. Society – and my mother – still expected a woman to become her husband’s property – if not in actuality, at least in spirit. My mother’s traditional salutation did puzzle me a bit. She demanded – and was paid - a salary from my father back in the 1960s for her work raising 7 children. She proudly had her own financial accounts all my life, and she was given the house they purchased in 1970 as she pointed out to my dad she did all the work to create our homes. From that point on, she owned the real estate my parents lived in, held in trust in her name only. And she made these demands from my father for equality before the 1974 creation of The Equal Credit Opportunity Act. That Act allowed a woman the right to open a bank or credit account, without a man signing for her. Yet here she was calling me “Mrs.” in 1987.

Interestingly, the 1980s saw a “backlash” against this feminism, and particularly against women’s ambitions. The “New Right” was growing, and targeted feminist issues – reproductive freedom, affordable childcare – in an effort to bring back “family values”; read: women stay home and have babies. Ms. Magazine had its own backlash. When Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, the first Black candidate for president, was on the May 1973 cover, almost all newsstands across the country declined to stock the magazine. When Alice Walker appeared on the cover in June 1982, newsstands in the South refused to display the magazine. “Steinem had imagined that a feminist readership with diverse interests and purchasing power would change advertising for the better. Instead, the pressure to please advertisers—publishing’s most concrete proxies for the powers that be—changed the magazine’s content for the worse.” (https://yalereview.org/article)

50 years later it seems we are still struggling to define what it means to be “feminist”. I have ideas that revolve around our patriarchal social structure, and all the ramifications of the Right’s political agenda. But it does me no good to harp on it; I only get more depressed and worried. So the best approach for me is to find joy in artifacts, recognizing the strength of the women who worked tirelessly before us to try to achieve something in the face of obstacles. No one said it was going to be easy to demand equality. History has a sad way of proving that point. And Krishna pointedly reminds us that compassion, protection and love take work.